For many years, the songbird had only emerged to sing on Christmas Eve, wound with utmost care by the mother and played once only at just the right moment as the highpoint of the festive celebrations around the family table. And for years, those at the table hadn’t known quite what to do: were they holding their breath to show due reverence to the poetry of the early 19th century? Or did they do it more out of fear that the little bird, having popped out and warbled, would break its neck completely as it retreated into the box, so infirm and unpredictable had the mechanism become?

To be on the safe side, the performances were recently recorded on a mobile phone, so that at least a video would exist should the songbird depart this life. But it wasn’t as though the recordings gave the family peace of mind, on the contrary: they only made everyone more nostalgic. The family had grown too fond of the snuffbox, too fond of the ritual of playing it at Christmas. So the family council decided to have the precious casket, its hidden mechanism and the bird examined and repaired and restored by every trick in the book.

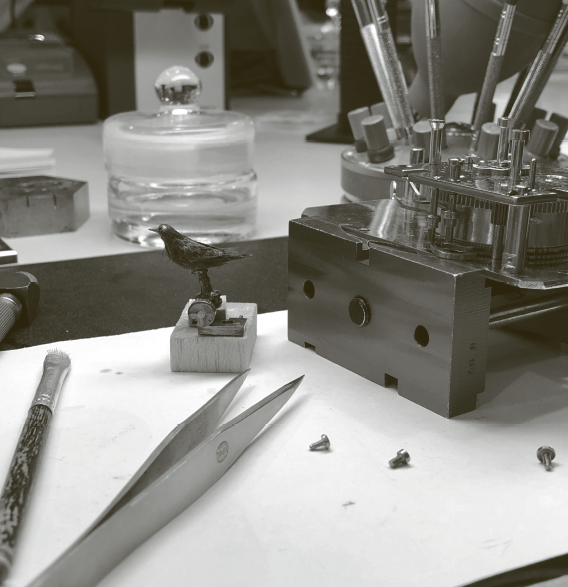

Only the specialists at the Beyer watchmaking workshop were considered capable of performing such an operation. More experience with historical mechanics would be hard to find; the team led by Damian Ahcin and Ernst Baschung is also responsible for servicing the exhibits in the Clock and Watch Museum – and has a reputation for not laying a finger on them until they have conducted thorough research and a historical examination of every screw. Each movement in the innards of the clockwork object is then also linked to cause and effect in the watchmaker’s mind, and of course meticulous records are kept of which parts correspond to the builder’s intentions and which have been added to over time or repaired more or (often) less expertly.

PRESERVING THE SIGNS OF THE TIMES

“Our top priority is to preserve the history of an object,” explains Damian Ahcin. Scratch marks, for example, are not simply polished away; after all, they bear witness to the pleasure that the object has given its viewers over the decades and centuries. Instead, these parts enjoy a bath in a drum with special solution and metal granules, in which the surfaces are cleaned by slow rotation. This prepares them optimally for subsequent lubrication. Now nicely spruced up, they continue to tell of the passage of time.

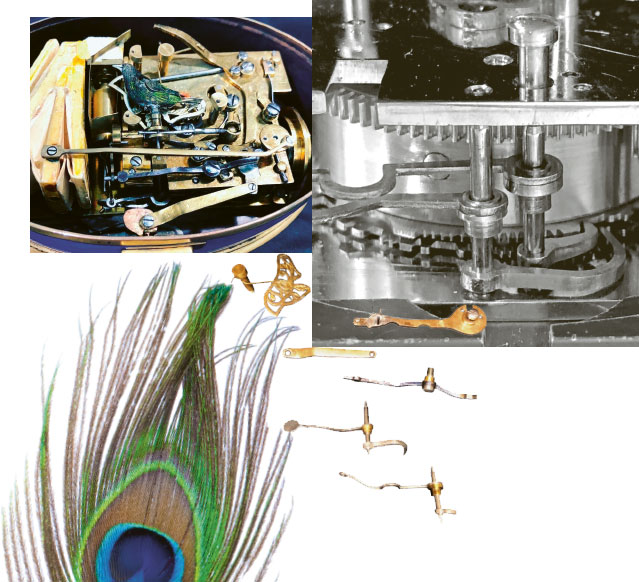

The great challenge with this songbird, however, was that the movements of the beak had to coincide precisely with the warbling being played by the tune disc through two small bellows on the organ pipe. This setting requires complex calculations, as the force of the wound spring passes through no less than three ratios, making it extremely difficult to regulate the energy. Especially because it was evident that other restorers who had been confronted with this problem before had disfigured the regulating mechanism with brutal drill holes. The mechanism that lifts the bird out of its recess and makes it move also proved tricky. Workshop co-director Damian Ahcin: “Various tiny parts had broken off, were jammed, drilled or soldered with tin solder. I doubt it would have lasted much longer.” The bird itself also needed a makeover: one side of its body was completely bald, and it had also lost an eye.

“I DOUBT IT WOULD HAVE

LASTED MUCH LONGER.”

Since the colourful, iridescent side is made of hummingbird feathers,which are no longer allowed to be used today, for the restoration of the featherless side Ahcin had to make do with peacock feathers, which he trimmed individually. A tiny red glass bead became a replacement eye. “Part of me is glad that this songbird is slightly more modern than some,” he says. “In the really old ones, it was not uncommon to use stuffed birds and cover the mechanics with the real skin of the bird.”

WHEN LEVERS FEEL THE RHYTHM

Next Christmas, when the magnificent blue casket is once again enthroned on the Christmas table, someone other than the mother might be allowed to turn the key this time: it won’t break off, but will wind up a cleanly oiled spring mechanism whose energy is regulated by the flywheel. The power sets the cam operating the flute mechanism in motion, compresses the leather bellows and snaps open the lid. It stands the bird up and moves the feathers, beak and tail. And when the three levers sense that the melody disc has reached its end, the bird will retreat back into its box. The lid will snap shut with that click that, in recent years, allowed the family to gratefully breath a sigh of relief. Only with the difference this time that no one has to worry whether the bird will survive. So it’s quite possible that its chirping will be heard not only on Christmas Eve, but throughout the Christmas season.